Never have we ever, neither within the healthcare profession, or outside it, seen, heard, smelt or tasted death, as it has been, like this before. In a time where so many things have been stripped from us, so suddenly and so heartlessly, it’d be almost laughable, wrong and unassuming to say this is anything but unexpected. Not in ‘these times’. And yet, as my healthcare colleagues become my carers; my doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, them too becoming my friends, I can’t help but grieve a whole different type of grieving when they are just clapped along, sunken by the stories of those who don’t make it, those who won’t last long, those who become the only victims of this crippling pandemic. Yet, as this becomes the norm to our daily grind, we shed very little light or hope on the stories of those who actively witness the ones on their deathbeds, the ones who, despite their hardest efforts, slip from the fingers of those who fight so hard to hold onto them, and who fight for us, most. When will we ask ourselves: What about those who are thrown into it all without choice? – thrown into one, eternal dark and dying moment – the things they must see, hear, smell and taste, every single day since this all began? Unimaginable, I hear you say…

For the past 7 months I have barely left the bedside. An endless, often gruelling hospital admission has marked me with this heavy feeling that I’ve missed out on life; missing out on the start of a new term of Medical School, those long conversations with family over the dinner table, Christmas, New Year, and now, even my birthday. But deep down, I also know that really, I have missed out on nothing, and that there are many others alongside me who are missing things way, way bigger…

On 30thDecember, 2020, 6.5 months into my inpatient stay, I tested positive for COVID19. I had been offered to be swabbed the night before by the staff nurse, after days of tears, pain, discomfort, and generally feeling vile since Christmas Eve, yet not really knowing why. But I hadn’t been anywhere. I hadn’t been ‘into contact’ with anything anywhere other than with the ward staff. Bedbound, hooked up, catheterised, and far too weak, I hadn’t even had to share the ward toilets with the other patients. I kept a collection of hand sanitisers by my bedside, and each (and the only) time I left the ward for procedures, I would be sure to mask up. So how could it possibly be COVID19? I shrugged half-heartedly, so obliviously convinced the test would come back negative, but also too ill to really care, either or. Regardless of it all, I had caught it; by the time I was swabbed I was so confused that I don’t even remember having the chest X-ray that was taken at the bedside that night, confirming the dreaded diagnosis.

I still consider myself extraordinarily lucky. Even the doctors said I was, given my endless background of underlying health conditions and hence shielding status. If anything, I was still very much sheltered from the true horrors of what COVID19 was flooring us all with up and down the country. I hadn’t read the news since the start of summer, but I knew that others around me were going through with it far worse, in that context. You didn’t have to ask or look deep into their eyes to know that. But they never showed it. Nobody ever complained, instead just getting on with their jobs as normal as they could, for the sake of all of us. Still, I was yet to experience the real dread, the hell in its rawest form, at least this time with my eyes open and mind somewhat still delicately intact.

I spent the next 2.5 weeks away in a COVID ‘red zone’ area of the hospital. In the beginning, this ‘red zone’ merely consisted of a small ward cut off from the rest, along with part of the Intensive Care Unit which was actively treating the worst-affected COVID patients. But now, this red zone has quickly expanded to the entirety of the hospital, consuming each ward with its misery and death sentence, all in blinking succession. Now, nowhere is free from it. We are heaving within the suffocating epicentre of the coronavirus.

Whilst endless news stories and miserable headlines have numbed our ears and minds, the personal accounts and stories of both survivors and caregivers thus remains today’s most matter-of-fact teachers of this pandemic. And I can assure you, on behalf of both my patient-friends and healthcare colleagues, that every single thing you hear and read are ruthlessly true to their every word. Of course, the account I am sharing with you here is nothing close to the madness of the ‘shop floor’ that most of us are hearing about in the media – the sorts that see ambulances queue for miles outside Emergency Departments and the critical care beds that are in such short yet desperate need that it is often a coin toss as to whether a patient gets their life saved or not. But the traumas I speak of, my traumas, although merely from the ward, a supposed safe-place, are still so applicably frightening. With that in mind, if thisdoesn’t open your eyes to what’s truly going on whilst you next mooch outside, go away on holiday or ‘pop’ round the neighbour’s for tea, then I really, really don’t know what will.

I had been lying in bed stark naked for 5 days running straight. There were no hospital gowns left on the entire floor, the COVID floor. Upon my bed, the black plasticky mattress was covered in a patchwork of nappies and Inco pads, in replacement of the bed sheets that they were also suffering massive shortages from. Incontinent, it was hard to disguise the bodily fluids that I sloshed around in, covered only by a single thin sheet that left me shivering and shuddering in the chill of my own vomit and urine that had been left to cool in my bed for hours. But there was never ever anyone around to clean me up. It wasn’t because they didn’t want to though. It was because they couldn’t keep up. And none of it was their fault. They too were sloshing, and sinking. Patients, previously fit and well just hours before, were now dying in crisis, just moments away next door. The staff hurried in, huffing and puffing, exasperated by the heat of their full PPE, slapping quiet our call bells, before quickly rushing out again, without asking what help we were in need of. We were left in an empty silence once more…

One night, the bone and muscle pain from COVID19 left me howling so much that I had to chew my pillow in an attempt to silence myself. The doors were sealed shut. The porters would come by to close them each time a deceased patient needed to be transported off the ward and over to the mortuary. In the beginning, this happened once, maybe twice, a week. Now they kept them shut permanently. I heard the numbers had soared that week I was there. I chose to stay looking away from that desolate corridor, and instead stared blankly towards the grey sleet sky, hanging emotionlessly through the cold-paned window.

“What now, Alex?! We don’t have time to see you!” they came storming in again. It was already turning into a very long night. I writhed in agony, gasping and grunting as I sniffed in the plasticky smelling oxygen supply through gulps, groans, and breathless sobs, unable to move. Eventually, the pain became so unbearable that I violently retched up the thick drainage tube that was in place up my nostril, into the back of my throat and down in my stomach. With the force of me vomiting, the tube coiled up into the back of my mouth, partially blocking my airway like a fat serpent on my tongue. Eyes streaming and face reddening, I gripped my neck tightly as big sticky bubbles of saliva foamed from my mouth. I gasped to the other patient to fetch help, but with my cries from the day before being shrugged off as me just being a nuisance, I was instead ignored and left to suffer, frighteningly, for another twenty minutes before anyone came…

At 5am I was rolled onto my front. It gave me short-lived relief, but my head felt as though it had been kicked into by one hundred horses, swimming to the opposite side of a beaten skull, neck rigid. I was left in that very same position, both call bell and phone well out of reach, until 2pm later that day. I had missed breakfast, and lunch too, with my total parental nutrition (TPN) still left unhooked, due to staff shortages and untrained agency nurses being the only available ones to administer our drugs. By mid-afternoon, a caterer finally came by, asking me timidly, and with caution, if I was thirsty. I was gagging. A beaker of fresh-poured boiling coffee was left on my bed, where I could reach it without moving. But my hand slipped, and with a lifeless swipe from a weakened grip, the beaker of boiling coffee spilt into my bed, splashing down my naked torso and into my pants. I couldn’t move. And it was scolding.

“Hot!” I shouted. “Hot!” Again, nobody came. Unable to shift myself, I lay lifeless, whimpering, searing from the sting of hot pain, chewing my pillow in silence once more.

When I mentioned the stiffness in my neck for the nth time, nobody listened. My head sloshed, I was vomiting, and the rigors seized up my muscles even more. Each time the sheer pain caught my breath, I had to stop myself from inhaling deeply, my lungs burning as though I was being gassed with a corrosive gale of sulphuric acid. Two hours later, a nurse finally came in.

“I have other call bells to answer”, she announced bluntly, before silencing my call bell and walking away. I pressed it again, begging for them to come, and to listen. She shuffled back.

“I could be doing lots of other things right now. I could be seeing lots of other patients. But no, instead I am having to stand here in front of you”. Through tears, I used my last sap of energy to speak up.

“You wouldn’t leave other patients lying in distress, would you?” She remained stood there, expressionless.

“But we’re not talking about other patients, are we? We are talking about you, Alex”. I suddenly felt very small and alone. Perhaps I had to ride this one out by myself. All these patients who were once people, were now just numbers, soon-to-be statistics, filling up beds, only to then leave them empty again, passing down another corridor, watched over by the solemn glare of another closed hospital bay. I wept for another moment, wondering if we really hadlost all the will to care.

In what felt like the final consecutive blow in that short space of time, the nurse came onto the bay and whipped my curtains open. I was inconsolable, and excruciating. Again, bed soaked in vomit and urine, now with the addition of crippling spasms from the other end too, all I wanted was a few moments of privacy and dignity to ‘ride it out’ myself, and alone.

“You need to stop crying Alex – it’s not fair on the other patients!”. This only broke me even more.

“Please”, I begged. “Just keep the curtains closed”. My bed filled up with faeces and urine, as I soaked through my hospital gown from the shivering sweat, the pain.

“Get your hands out of your backside Alex, and be quiet!” the nurse snapped again. I could hear the other patients on my bay snigger. I cried out for my Mum, utterly broken. Upon her final storm to my bedside, this nurse snatched my phone out of my hands and moved it, and the call bell, well out of my reach. I had nobody. There was nobody I could call out to and nobody I could turn to for help. Not even my own Mum on the end of a phone-line. The room felt deathly and hollow.

It was never not unsettled. As I lay there, helpless and scared through all of this, I felt mocked. Other patients argued in the background over the COVID19 swabs and who was negative and who was positive. Patients blamed each other for either catching the virus or passing it on, as we were shut off into a fortnight of isolation once again. Everyone felt it. Everyone felt personally attacked by the stress and worries taking their toil. This is what fear in a pandemic was doing to us. Yet throughout this entire time, nobody could source a single moment to listen. My fears were these empty calls in an empty body of a room, where nobody had noticed I was growing even more poorly, on top of a COVID19 diagnosis. Little did anyone have time to stop or realise that I was growing septic, a nasty Staph A infection in my bloodstream that would soon send me into long-raging fevers of 39-40’C and an infected blood clot in my neck; the vessel leading to my heart.

“For goodness sake Alex, your neck is not fractured!” was all that they would say, before rushing off to the next patient. And then the next.

Despite the catalogue of traumas I experienced over those few weeks, I have complete forgiveness for all the staff – my colleagues, my friends. Beyond everything, the COVID19 pandemic has not only taught me to be grateful for every little thing I do have, but also to be forgiving, in a time where we are met with nothing but incredibly unforgiving circumstances. I know that I will never truly see, hear, smell or taste the same guilt, grief, tears or loss that they have, and continue to, experience, on a daily basis. And through all the PPE, where nobody has seen behind the mask for so many months, I still recognise, still know, the familiar glint of kindness, the glittering smile, through the conceal of pain, in all their eyes, wholly oblivious to the fact they’ve just returned from crying in the staff toilets, or their internal questioning on when they’ll next be in work if they haven’t themselves fallen victim to the virus they fight face-first every day.

Another nurse, both an amazing colleague and a great friend, came back to me one afternoon and knelt down by my bedside.

“This is not what I came into nursing for”, she swallowed hard. “This is not acceptable and I am SO sorry this has happened to you”. There was another long pause of silence, another invisible tear in both our eyes. It was honestly all I wanted and needed to hear. Because I already knew. She cared. She really, really cared, and yet deep down, beneath the deafening noise of our Thursday claps and the constant ring of bedside call bells, she was suffering, drowning, and grieving too.

I recently plucked up the courage to ask for some help to get me through this time, through the form of counselling. After 7 months in hospital, a rough time with COVID19, and now a close-call with sepsis too, I felt it was only right I share my traumas with someone else who may understand, before it takes its toil far beyond this turbulent time. Sadly though, in every kind of irony, whilst it took only hours to send someone up at a time when a point was wanting to be made by an unconvinced doctor – not believing any of my underlying symptoms, now when I really needed it, for the greater good, I couldn’t have it. It was another empty call. But am I the slightest bit surprised? No. Why? We are all waiting to share our stories, our own lurking traumas and COVID19 horrors that are forced back down underground with all our fallen patients. Just how long are we expected to keep these things hidden though? Who knows how long we will all be waiting until the mental health of our healthcare profession is recognised and alerted to as just as great a public health crisis as the pandemic itself?

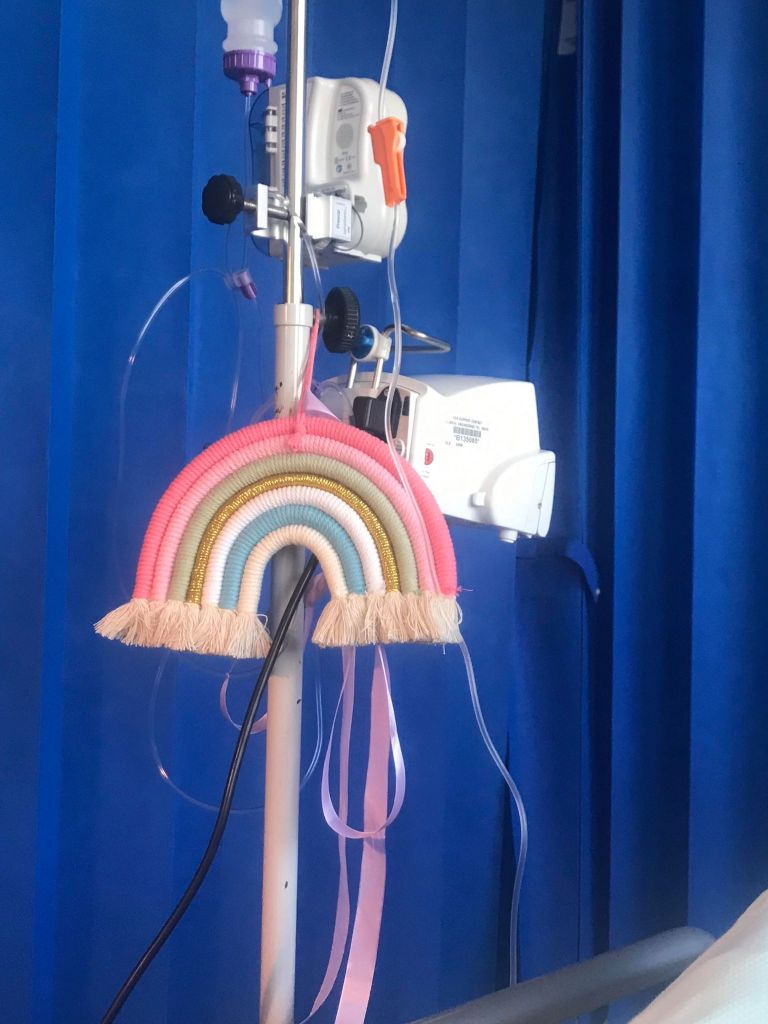

I am incredibly lucky, and having celebrated my birthday just days ago, albeit stuck in hospital and so far away from any human contact, hugs or family for it, I am so utterly grateful just to be here. Because I know it’s something that others have been less fortunate with. It may sound silly or simple, but gratitude and forgiveness are both far greater a gift than anything else I wish materialistically for 2021 and beyond. The commitment, the love and the pure selflessness of every single person, carer, provider, hero, continuing to push through in a time of such horror is one precious positive this pandemic has not produced, but finally brought out for overdue respect and recognition. This year, I received birthday cards from healthcare assistants who have cared for me, and from my favourite caterer too. I was over COVID19 and sepsis enough to be able to enjoy the snow, taste a pink birthday cupcake, and facetime my beautiful family over 200 miles away, and I honestly couldn’t have asked for anything better. The only other thing I truly wish for now is for the rest of you, the general public, to really look, listen, stop and appreciate that COVID19 really is real, really is horrid, and really can, and WILL kill, if you don’t start listening to our stories now, and taking responsibility for it. In all of this, it’s now down to you to save us – for all our grandparents, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, daughters and sons, calling out in those closed and empty, silent rooms…

I’m absolutely staggered by your story and what you have been through.

You are far kinder than most, I think some of the behaviour towards you was despicable.

I’m truly horrified.

You poor, poor girl xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you.

I’m sorry, I don’t know how to put my feelings into words. thank you for sharing this and for making me a part of your story.

I’m greatful you’re able to share your account with us.

sending you strength, love and hope from the other side of the world.

love from India

LikeLiked by 1 person

There would be no forgiveness on my end for that nurse. Her incompetence nearly left you to die. Never mind the emotional abuse and gaslighting at the hands of A person in the caring profession. I’m sorry you went through all of this alone and unheard. I honestly have no words except to say how incredibly strong and resilient you are, patient, kind and forgiving. There are not many people in this world like you Alex. xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

So sorry this has happened to you – you are amazingly strong to get through it and to publish such a vulnerable and beautifully written account of it too. Sending you love xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds just awful, hospitals are struggling more than ever, I’m sure that lawyers will be running their hands with glee during this pandemic. I don’t know why anyone would become a nurse right now. I really hope the younger generation stay away from this absolutely impossible career.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, I am an NHS doctor, and have been for over 10 years. I’ve worked on understaffed wards, and have seen patients get suboptimal care as a result. However, reading this really horrified me.

The nursing staff have a duty of care to you. They have completely failed in this. This is not only a very serious safeguarding issue, but in fact appears to verge onto abuse (putting your phone out of reach.) Whilst I applaud your forgiving attitude, there is absolutely no justification for this whatsoever – pandemic or no pandemic, the hospital has failed you. I would also be very worried that other vulnerable patients would also be victims of this abuse and neglect.

If you have not done so already, I would strongly urge you to consider raising a formal complaint about how you were treated – otherwise, the hospital has no reason to acknowledge the mistreatment of its patients, and no reason to try and address it, and staff will continue to mistreat patients. Not only will such treatment deprive patients of their dignity and will be emotionally damaging, but it will also increase their chances of getting serious and even life-threatening hospital-acquired infections. Complaining is not about placing blame or being vindictive, but is about highlighting major flaws in care, that are in fact very serious patient safety issues.

A good hospital would investigate the reasons this happened, and take appropriate corrective action, whether it is addressing the reasons for a single individuals conduct, or in fact looking at staffing levels and workload on the ward as a whole and potentially trying to increase staffing. What has happened to you would (in my view) reach the threshold for being considered a Serious Incident, and deserving of detailed remedial action. There is absolutely no world in which this kind of situation is OK, or should be accepted.

I would also consider asking if, in light of this mistreatment, a single member of your family could be allowed to visit periodically, as a safeguard against further such mistreatment.

I wish you all the best with your ongoing care, and hope that you manage to get home soon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Alexandra, who celebrated her 27th birthday in hospital at the end of January, has been blogging about her medical studies and her stay in hospital, and one particular entry as the hospital dealt with the second spike in coronavirus at the start of this year. You can see Alexandra’s blog here. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person